When Vladimir Putin launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, he did so from an acute strategic calculation underscored by imperial nostalgia. Russia’s ambitions were rooted in a pragmatic desire to preserve access to warm-water ports and secure dominance over the Black Sea; to prevent NATO’s military footprint from extending to the doorstep of the energy-rich Lower Don basin; and to reassert Moscow’s role as the arbiter of Eurasian and, by extension, global security. For the Kremlin, the war was meant to reclaim what it viewed as historically and strategically indispensable territory, while simultaneously reviving a resurgent “Russian world”. A civilization bound by culture, faith, and shared destiny that would naturally be led by its historical hegemon. While Putin may not have designs on undoing the collapse of the Soviet Union, he recognizes that the long arc of Russian history has not reached a conclusion but rather a stumbling block to be overcome through decisive action.

“All NATO countries are fighting us, and they’re no longer hiding it … A centre was created specifically in Europe, and it essentially supports everything the Ukrainian armed forces do. It feeds information, transmits intelligence from space, and supplies weapons and gives training.” – Vladimir Putin

Three years later, the results have been the opposite of what Moscow intended. What began as a bid to restore Russia’s geopolitical reach has instead exposed the limits of its power. The Russian economy, restructured around wartime production and constrained by sanctions, now survives through coercive mobilization. Opportunistic and arguably unfavorable trade terms with China, India and middle powers in their extended periphery show the increasing desperation of the Russian regime to salvage its economic connections with the East as they have frozen themselves out of the West. Russia’s military, which was once touted as the second most powerful in the world, has revealed itself as brittle and technologically inferior. From its early history Russia’s military doctrine has always depended on sheer manpower, but it has recently endured the embarrassment and logistical problems that accompany conscription of penal battalions and mercenary units armed with outdated Soviet stockpiles.

Yet despite these shortcomings, Russia endures and Ukraine falters. Ukrainian manpower has thinned after years of attritional warfare, Western support are growing increasingly uncertain as the taste for war in both the United States and the rest of NATO is virtually nonexistent. With some fronts completely abandoned by the Ukrainians, who leave only land mines behind to dissuade an aggressive offensive, the spectre of a major Russian breakthrough remains a constant threat. Still, the cost to Russia of maintaining their war footing in the face of (albeit sporadic) western support of their adversary has been staggering between vast material losses, the exposure of deep structural weaknesses, and the corrosion of Russia’s credibility as a modern power.

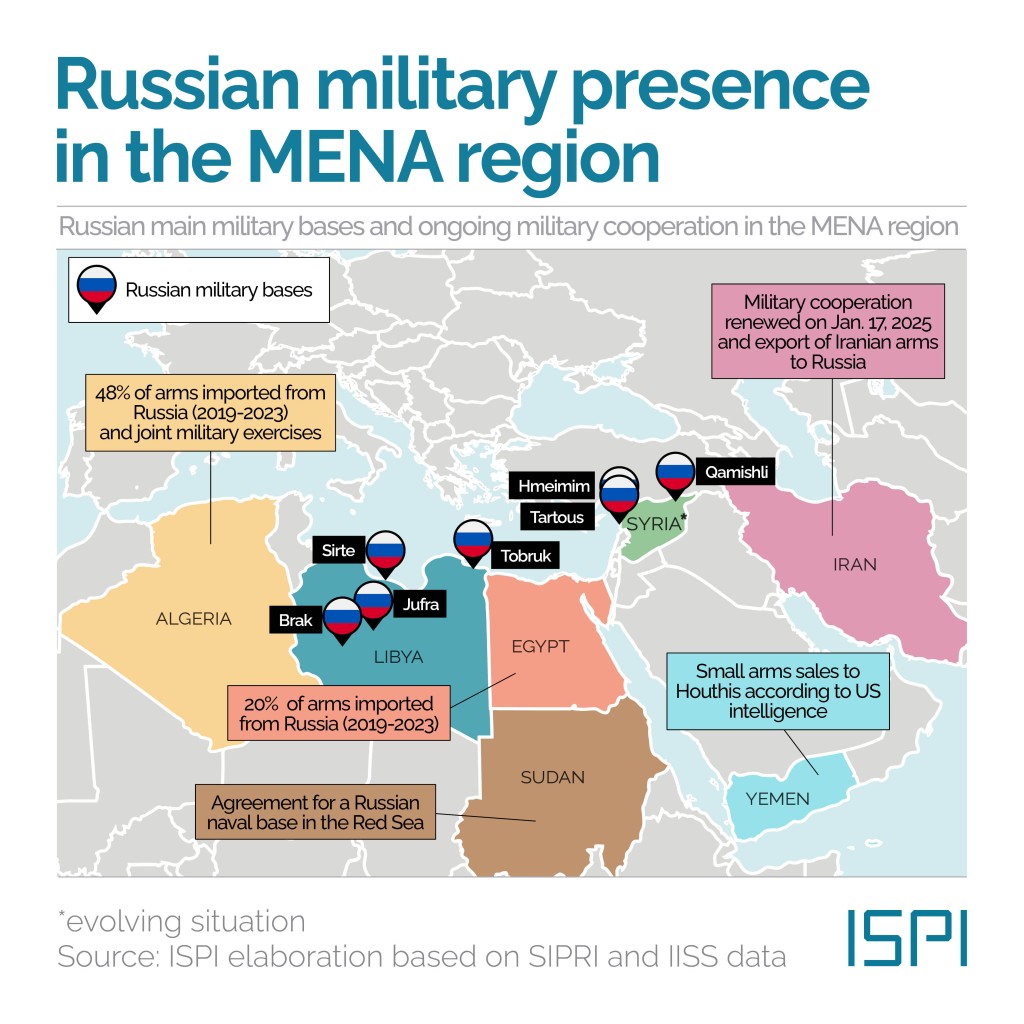

Most striking of these costs is the erosion of Moscow’s diplomatic standing. The invasion intended to solidify Russia’s influence over post-Soviet Eastern Europe has instead alienated its closest partners. Armenia, disillusioned by Moscow’s failure to uphold defense guarantees, has distanced itself from the Collective Security Treaty Organization and turned westward. In Central Asia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan now pursue foreign policies increasingly independent of Russian direction, deepening their relationships with China, Turkey, and the European Union. Even beyond its traditional sphere, Russia’s reach has receded. The fall of the Assad regime in Syria marked the effective collapse of its only long-term client state in the Middle East, while its unwillingness to intervene on Iran’s behalf during the Twelve-Day War signaled to regional powers that Moscow no longer possesses either the capacity or the will to shape events beyond its borders.

Russia thus finds itself at a paradoxical crossroads: militarily aggressive but strategically constrained, economically active but structurally weakened, diplomatically engaged yet increasingly isolated. Its claim to regional leadership no longer rests on shared purpose or cultural gravity, but on inertia and coercion. This essay examines the foundations and consequences of that decline. It explores how Russia’s economic distortions, military burdens, and diplomatic failures have combined to hollow out its strategic position, and how former allies such as Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan are asserting new independence as a result. Ultimately, it argues that in pursuing dominance through force and fear, Russia has hastened the unraveling of the very empire it sought to restore.

The Economic Undercurrents of Decline

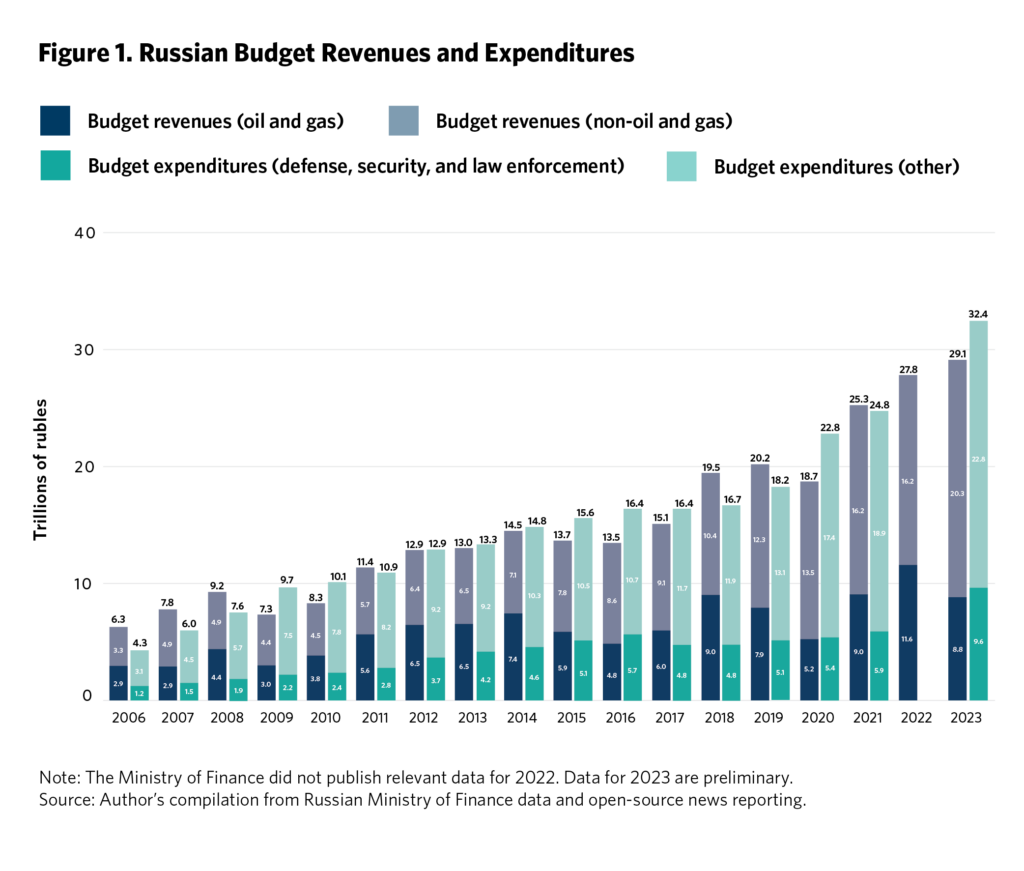

Russia’s capacity to wage prolonged war has often been misunderstood in Western analysis. Despite predictions of economic collapse following the invasion of Ukraine, Moscow’s economy has proven more durable than anticipated. This resilience, however, conceals Russia’s fundamental transformation from a modernizing, semi-market economy into a militarized command structure reminiscent of the late Soviet model. What appears outwardly as stability is in reality a system sustained by coercion, improvisation, and foreign dependence. The Russian state has kept production humming by converting civilian industry to military use, imposing strict capital controls, and leveraging its natural resources for political ends. The long-term consequences will be unmistakable as the economy at large will continue to be hollowed-out; increasingly reliant on wartime output, cut off from innovation, and structurally incapable of sustained growth.

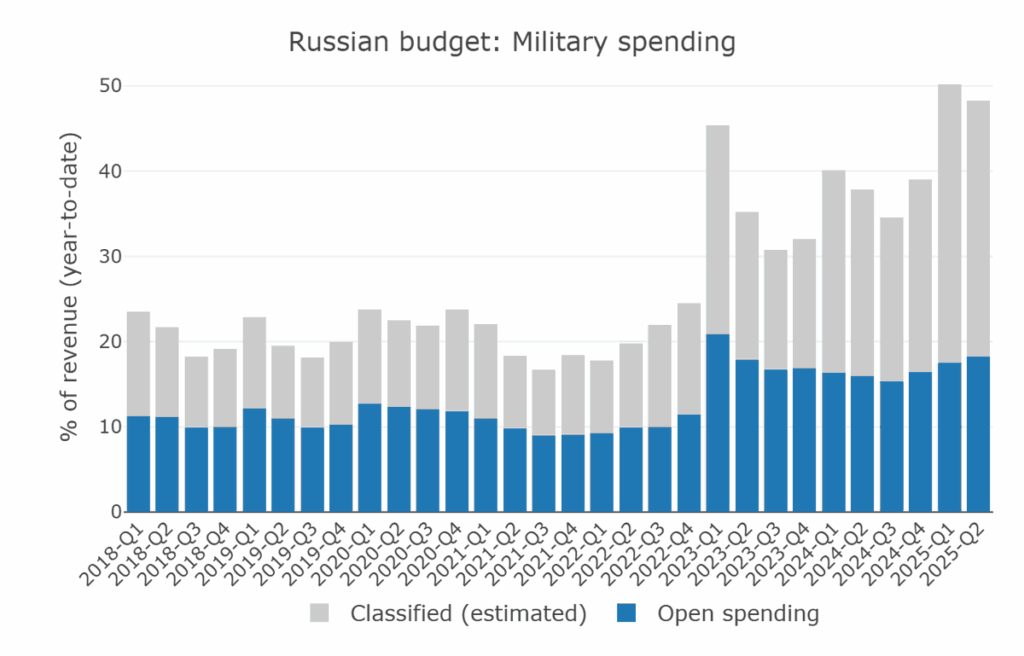

At the heart of this decline lies the war economy itself. Since 2022 defense has consumed more than a third of the national budget. The result has been an artificial surge in employment and industrial activity as uneducated laborers flock to tank factories, ammunition plants, and drone assembly lines working around the clock to meet front-line demand. While this same kind of mobilization created the American industrial golden age, in Russia this growth is narrow, unproductive, and unsustainable. During the Second World War, growth in wartime industries was supplemented by the expansion of the civilian private sector, but due to the Russian conflict’s proximity to their productive infrastructure, civilian industries have been all but cannibalized to feed the war machine, leaving consumer goods scarce and prices volatile. Simultaneously, labor shortages, driven by mass mobilization and the exodus of skilled professionals, have further strained productivity. Hundreds of thousands of Russia’s most educated workers from engineers and scientists to IT specialists have fled to Armenia, Georgia, and the West, draining the very human capital that once underpinned Russia’s technological aspirations.

On top of all this, sanctions have deepened these structural distortions. Cut off from Western capital markets and advanced technology, Russia has turned to parallel import networks through Turkey, Kazakhstan, and China to acquire restricted goods. These workarounds sustain the military effort but erode efficiency and innovation, not to mention breeding new layers of corruption. The Russian financial system has survived by rerouting trade in rubles and yuan, yet at the cost of increasing dependency on Beijing; a relationship that now borders on subordination. Energy exports, once the pillar of Russian economic strength, have been redirected eastward but at steep discounts, forcing Moscow to sell oil to India and China at prices far below market value. The state has preserved short-term liquidity, but its fiscal stability rests on a fragile foundation of depreciated currency, mounting deficits, and diminishing access to hard currency reserves.

Even the apparent resilience of Russia’s GDP tells a misleading story. Official figures project modest growth, but once again that growth is overwhelmingly military in character. This may not be a problem when you can count on the assembly lines carrying tanks to carry consumer vehicles in the near future, but the Russian production of materiel is constantly under threat from US supplied long range missiles, and so investment in expensive dual-use infrastructure is out of the question. As a result the increase in Russian military production neither enhances civilian welfare nor creates enduring economic value. Infrastructure development, private enterprise, and technological innovation have all been submitted to state control. The Kremlin’s rhetoric of self-reliance and “fortress economy” may rally nationalist pride, but it masks the reemergence of Soviet-style inefficiencies that mark all states engaged in central planning; waste and dependence on hostile foreign markets for raw material exports. Ordinary Russians bear the brunt of this economic restructuring through rising inequality, inflation, and a shrinking standard of living, even as propaganda paints the illusion of patriotic prosperity. The common opinion among Russians was once that so long as Putin can project Russian power abroad and protect our interests at home, then an aggressive foreign policy in the Middle East, Central Asia and most recently Eastern Europe is beneficial to the end of maintaining regional leadership. This opinion is now only shared by an obstinate minority that refuses to admit that though the Russians may prevail in their limited objectives, they will ironically exit this war far weaker than they were at its zenith.

The economic trajectory of modern Russia is therefore functional but only to serve the perpetuation of war. The state’s ability to command resources ensures short-term survival, but every measure taken to sustain the conflict erodes the long-term vitality of the nation. A durable great power requires innovation, diversification, and trust while Russia’s war economy is gripped by stagnation and fear. In pursuing total mobilization, the Kremlin has sacrificed the very foundations of its strategic endurance, creating an exhausted empire sustained by momentum.

Military Realities: Power Without Precision

For two decades, Russia sought to project itself as a modern military power capable of challenging the West. Exercises and exhibitions like Zapad and Vostok, reforms under Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and high-profile weapons showcases in the Middle East created an image of precision, professionalism, and strength until the war in Ukraine shattered that illusion. What the conflict has revealed is a military that remains deeply inflexible, and plagued by corruption. Against its will, it has proven effective at sustaining attrition but it is altogether incapable of rapid maneuver or integrated modern warfare. Its early failures in 2022, from the disastrous advance on Kyiv to the chaotic retreats in Kharkiv and Kherson, reflected tactical errors as well as systemic dysfunction. Its poor logistics, fragmented command structures, and an overreliance on dubious intelligence proved that the former “second army of the world” is unable to achieve its objectives against a far smaller but better-motivated adversary.

Nevertheless, Russia’s military performance, though marred by ineptitude, has evolved. Through adaptation born of necessity, Moscow has learned to sustain a long war of attrition; one that favors its demographic size, industrial mobilization, and tolerance for loss. The Kremlin’s willingness to absorb staggering casualties has allowed it to stabilize front lines, especially as Western support for Kyiv faces political headwinds. Ukraine, by contrast, faces growing manpower shortages after years of high-intensity conflict. Videos circulate online almost daily of Ukrainian men being dragged from the streets kicking and screaming before being sent to the front lines where their ever shrinking units will be expected to control ever growing sections of territory and to fill the gaps with antipersonal ordinance that will render these battlefields uninhabitable for generations to come. Its dependence on Western arms and financing, while essential, makes it further vulnerable to fluctuations in political will abroad. Russia has exploited this imbalance through relentless pressure along the eastern front, seeking to wear down Ukraine’s capacity for resistance rather than achieve a decisive breakthrough.

We cannot ignore, however, that these tactical adaptations have come at enormous strategic cost. Russia’s losses in manpower and equipment are unprecedented in the postwar era: hundreds of thousands killed or wounded, thousands of tanks and armored vehicles destroyed, and elite units decimated beyond recognition. To replace these losses, the Kremlin has turned to mobilized conscripts, penal battalions, and mercenaries. These measures have preserved numbers but degraded quality, discipline and professionalism. Modern precision warfare demands synergy in intelligence, air superiority, and logistics; all of which are capabilities Russia has failed to master. Despite battlefield successes in localized sectors, Moscow’s inability to integrate combined arms operations or secure sustained air dominance underscores a deeper truth. Its reliance on attritional tactics against Ukraine make it completely impotent against other major powers.

The technological disparities are equally revealing. Russia’s reliance on Iranian drones, North Korean munitions, and repurposed civilian technology illustrates how sanctions have constrained its military-industrial base. Its once-vaunted defense sector now depends on improvisation and sourcing from states that, like Russia itself, are disgraced and unintegrated with the global community. Recycling Soviet-era stockpiles and retrofitting outdated systems to meet modern demands are common patterns in recent developments. This contrasts with American-supplied Ukrainian weaponry; precision artillery, modern air defenses, as well as digital battlefield networks and real time intelligence and high speed communication supplied by SpaceX’s Starshield. While the Kremlin boasts of hypersonic missiles and nuclear deterrence, these capabilities remain strategically irrelevant to the grinding reality of a land war fought with artillery, drones, and infantry.

Internally, the prolonged conflict has exposed the fragility of Russia’s command structure and morale. Information is tightly controlled, but reports of low morale, corruption, and desertion within the ranks are widespread. The opaque power struggle between the Ministry of Defense and private military groups, culminating in the Wagner mutiny of 2023, revealed the extent to which the Kremlin’s control over its own instruments of violence has eroded. Even as the rebellion failed, it shattered the illusion of cohesion at the heart of the Russian state. The war has thus also become a stress test of political stability as well as military endurance, binding the regime’s survival to the war’s success.

In sum, Russia’s military has demonstrated that it can persist, but not prevail in the manner of a true great power. The war has laid bare Russia’s unique strategic predicament: a nation capable of enduring immense sacrifice but incapable of translating that sacrifice into lasting advantage. In the process, Moscow has expended not only men and materiel, but the credibility of its armed forces and revealed to allies and adversaries alike that its power, though vast, is imprecise and unsustainable.

Diplomatic Collapse in the Near Abroad

For three decades after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Moscow’s foreign policy sought to preserve a sphere of influence across Eurasia. A buffer zone of states tied to Russia through economic dependency, security guarantees, and shared institutional frameworks like the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) would insulate Russia from exterior threats and incursions and its leadership in these intergovernmental organizations may eventually put them on a path to future reintegration. This “Near Abroad” was central to the Kremlin’s self-image as a global power. In the wake of its loss of a true empire, Russia could maintain an informal sphere sustained by carrot and stick diplomacy, energy leverage, and elite patronage. Yet since 2022, that system has begun to unravel. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned several allies into skeptics, and skeptics into quiet adversaries.

Armenia: Abandoned Ally

Nowhere is this shift more visible than in Armenia, once among Moscow’s most dependable clients in the Caucasus. For decades, Armenia’s security, particularly against Azerbaijan, depended on Russian protection through the CSTO and the presence of Russian troops stationed in the Gyumri Russian military base. But when renewed conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh erupted in 2023, Moscow’s response was strikingly muted. Despite treaty obligations, Russia refused to intervene decisively, prioritizing its war in Ukraine and its fragile partnership with Turkey over Armenia’s security. The Kremlin’s passivity in the face of Azerbaijan’s offensive shattered Yerevan’s faith in Russian guarantees.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s subsequent overtures to the West were received with open arms and led to military cooperation with France, EU observer missions, and growing engagement with the United States marking a profound geopolitical realignment. Armenia, long viewed as firmly within Russia’s orbit, is now actively abandoning its largest patron of the last two centuries. The collapse of the Armenian position in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023 may have seemed to expose Russia’s distraction to the outside observer; but in Armenia it symbolized the death of Moscow’s credibility as a regional guarantor. The CSTO, once a key instrument of Russian soft power, now appears to be a hollow defensive pact whose members can no longer rely on or trust its leader.

Central Asia’s Quiet Defection: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

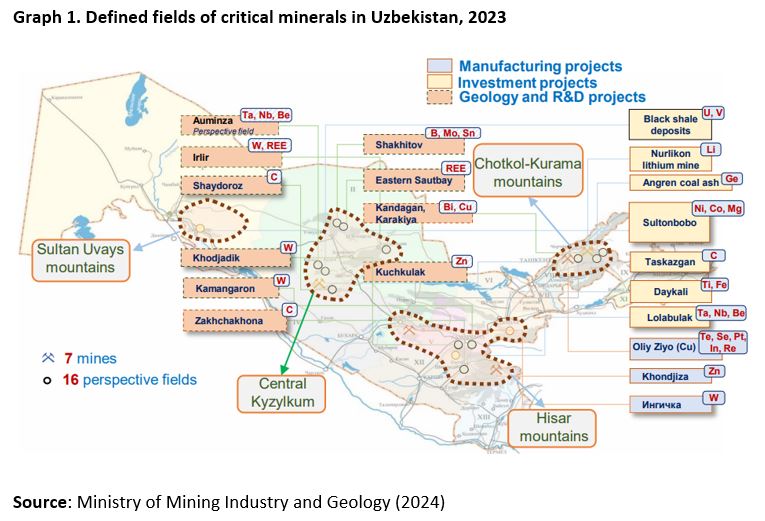

The erosion of Russian influence extends deeply into Central Asia, a region historically tethered to Moscow through trade, migration, and shared security concerns. Kazakhstan, the largest and most economically significant of the Central Asian republics, once viewed Russia as an indispensable partner. Yet since the invasion of Ukraine, Astana has distanced itself carefully but unmistakably. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has publicly refused to recognize the annexed Ukrainian territories, while pursuing closer ties with China, Turkey, and the West. The irony is acute: in early 2022, Russian forces helped suppress unrest in Kazakhstan under the CSTO framework, but that brief intervention did not translate into loyalty. Instead, it underscored Astana’s vulnerability and the danger of overreliance on Moscow. Today, Kazakhstan’s growing economic integration with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and its diplomatic balancing between Russia and the West, illustrate a pragmatic recalibration away from dependency.

Uzbekistan, though never a formal CSTO member, likewise reflects a regional pivot. Tashkent has expanded cooperation with Western institutions, avoided taking Russia’s side in international forums, and embraced multilateralism through non-Russian mechanisms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The Uzbek leadership views the Ukraine war as a cautionary tale and proof that Russia’s security partnerships can become liabilities overnight. Both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan now position themselves as sovereign actors capable of playing larger roles in Eurasia independent of Moscow’s guidance.

The Symbolic Decline of Integration Projects

The weakening of the CSTO and the EAEU further underscore Moscow’s diminishing diplomatic gravity. These institutions once embodied Russia’s aspiration to create a Eurasian alternative to Western alliances. Today, both are little more than bureaucratic shells. The CSTO’s failure to act in Armenia’s defense and the EAEU’s inability to shield its members from Western sanctions reveal that these alliances were never more than mechanisms of control that became inconvenient obligations when Russia decided to prioritize its own territorial ambitions. As Russia’s power wanes, so too does the willingness of member states to accept its dominance.

Meanwhile, China’s ascent as an alternative regional hegemon compounds the problem. Beijing’s expanding economic footprint through infrastructure, technology, and investment offers Central Asian states tangible benefits that Moscow can no longer provide. The result is a clear divvying up of middle powers between East and West while Russia is gradually being torn apart from within and without.

The Middle East and the Loss of Peripheral Influence

Beyond the post-Soviet sphere, Russia’s strategic overreach has cost it its only reliable foothold in the Middle East. The collapse of the Assad regime in Syria marked a symbolic end to Moscow’s presence as a decisive regional actor. The 2015 intervention to rescue Bashar al-Assad and aid pro-government forces against ISIS, was heralded in Moscow as proof that Russia could project force beyond its near abroad, securing both a client state and lasting bases at Tartus and Latakia. Syria’s eventual disintegration exposed the fragility of Russian commitments abroad. As Iranian and Turkish forces filled the vacuum, Moscow has proved unwilling and unable to sustain the financial and military burden of propping up Damascus.

Equally telling was Russia’s inaction during the brief but consequential Twelve-Day War, when Israel and Iran clashed directly in a regional escalation. Despite its longstanding partnership with Tehran, Moscow remained on the sidelines, unwilling to risk confrontation that would further deplete its resources or even offer rhetorical backing during the confrontation. In doing so, it signaled to the world that its capacity for influence beyond Europe has all but collapsed.

Even beyond the battlefield, Russia’s soft power across the Middle East has atrophied to near irrelevance. Arms sales have plummeted as clients turn to cheaper, more advanced alternatives from China and Turkey. Cultural diplomacy, once sustained through educational exchange and media presence, has faltered amid sanctions, censorship, and the global isolation of Russian institutions. Even the narrative of “multipolarity” that once resonated with states seeking to hedge against Western dominance now rings hollow. In the vacuum left by Russia’s withdrawal, China, Turkey, and Gulf powers have surged forward to fill the void once contested by Moscow. It is unclear whether the Kremlin’s inability to uphold commitments in Armenia, command loyalty in Central Asia, or sustain influence in the Middle East reflects temporary weakness or irreversible structural decline, but no matter the case, major and middle powers are wasting no time in taking advantage. The empire of influence Moscow once maintained through fear and patronage is dissolving and with it, the foundation of its great-power identity.

Conclusion: The Price of Restoration

Russia’s pursuit of imperial restoration, from Ukraine to the broader post-Soviet space and beyond, has revealed the profound limits of coercive power in the 21st century. What began as a calculated effort to secure strategic ports, energy corridors, and geopolitical prestige has instead exposed the structural weaknesses of the Russian state. Economically, the war has converted productive industry into a fragile war economy dependent on central planning, discounted energy exports, and a dwindling pool of skilled labor. Militarily, Russia’s armed forces have demonstrated endurance at the cost of precision, innovation, and legitimacy, exposing vulnerabilities in logistics, technology, and command that were previously obscured by propaganda and selective modernization. Diplomatically, Moscow’s retreat has been even more consequential. Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have all reoriented their foreign policies toward autonomy, diversification, and pragmatic engagement with powers beyond Russia’s orbit. In the Middle East, the collapse of Syria’s Assad regime, Moscow’s inaction during the Iran–Israel conflict, and the declining appeal of Russian soft power signal the erosion of influence once thought to be ironclad. Across the globe, the narrative of a “Russian World” has faltered, replaced by skepticism, opportunism, and the rise of new multipolar actors such as China, Turkey, and regional powers in the Gulf.

It is important that we as Americans recognize that Russia remains a formidable power, despite these recent embarrassments. It is nuclear-armed, resource-rich, and capable of projecting force in localized theaters. Its influence is not extinguished, but it is now constrained, contingent, and increasingly transactional. The Kremlin’s remaining authority rests less on legitimacy or soft power than its reputation to resort to kinetic conflict and the scarcity of alternatives for its neighbors.

Ultimately, Russia’s trajectory illustrates that military might and historical legacy are insufficient without credible alliances, sustainable economics, and the ability to project influence beyond immediate borders. Moscow has incurred extraordinary costs in the form of Russian lives, resources, and global credibility in the pursuit of modest strategic gains. Time will tell if this conflict was worth it in the eyes of the Russians but we can conclude that thus far their empire has been hollowed from within, leaving a weakened state that is watching as its once impenetrable sphere of influence is picked clean by great power competitors.

Leave a Reply